Many of you reading this post know about my idolatry of Alice Munro's short stories and literary legacy. I did not know her personally. In a previous post, about a month ago, I wrote about how, over the past few months, I have had little opportunity to organize my writing time on Substack. Nevertheless, in the days after Munro's death, I was compelled to visit Clinton and Wingham twice to honour Munro and offer random thoughts about the writer who influenced me the most.

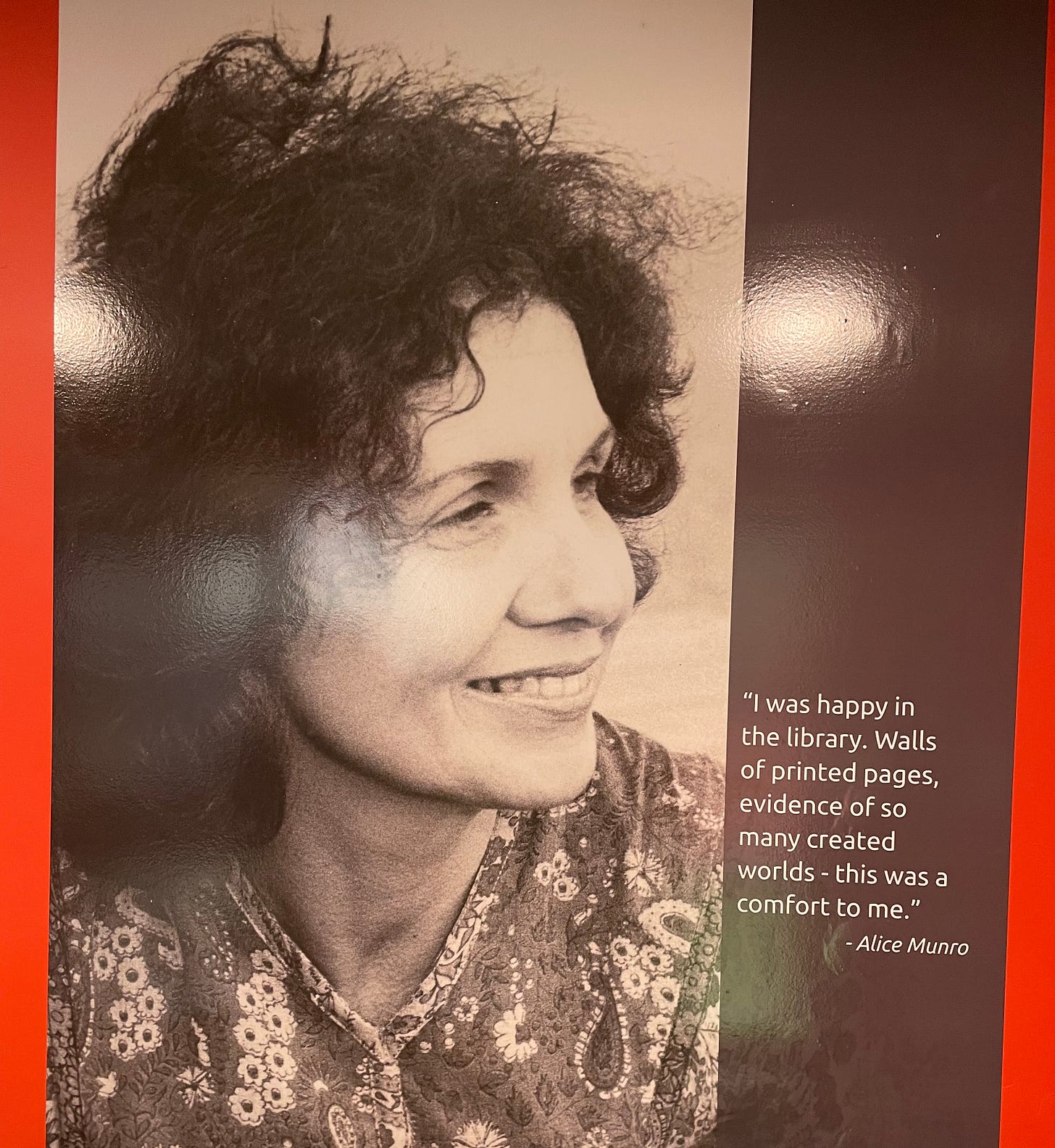

Until a few days ago, I have been working diligently on curating an experiential Alice Munro Literary Trail that I had hoped to launch next year. I think that many of you are likely familiar with Munro's oeuvre, but for those who are not, Munro, a southwestern Ontario native, died on May 13, 2024, at 92. She was among the most respected and lauded Canadian contemporary short story writers (alongside another of my favourites, Mavis Gallant). Munro, a national treasure was awarded the Booker Prize and in 2013 the Nobel Prize for Literature. Her prolific essays, many published in the New Yorker (60 at last count), established Munro's international reputation as a master of short stories compared to writers from Thomas Hardy and James Joyce to Willa Cather. She is “our Chekhov, our Flaubert.” Many consider her essays among the most critical, rich in subplots, movement in time and ancillary characters.

Munro grew up outside Wingham, Ontario, with a long walk to and from school. To pass the time, she created stories and started putting them on paper when she was 10 or 11. She went on to study English and journalism at Western University (which has long publicized its association with Munro and, since 2018, has employed an Alice Munro Chair in Creativity and is now considering how to move forward given the recent revelations) before moving to British Columbia when she was 20.

I recently visited Munro's former home (her second husband, Gerald Fremlin’s family home) and the iconic Bartliff's Bakery (a Huron County tradition since 1902, and a favourite haunt of Munro's and mine) in Clinton numerous times in the past months. I have travelled the road she walked to school, visited and photographed the exterior of her childhood home in Wingham, and, on three occasions, the Alice Munro Literary Garden and the Alice Munro Library. The librarian told me that unidentified family members had been to visit the Alice Munro Library to see the original exhibit a few days earlier when I visited in early June.

I have spoken with out-of-town visitors to the Literary Gardens about her short stories and with Wingham locals about Munro on the street. I even met a 25-year-old green-winged macaw named Casey, whose extroverted owner had much to say about Munro. Last week, on vacation, I visited the new Alice Munro exhibit at the Alice Munro Library for the Wingham Homecoming 2024. On another occasion, we were greeted by an elderly, friendly farm dog when we stopped by the pastoral Blyth Union Cemetery, where Gerald Fremlin, is buried. I read that Munro planned to be interned alongside him. The nondescript site and headstone did not feel fitting for a person of Munro’s stature.

Little did I know what lay ahead. Gerald Fremlin's sexual abuse of his step-daughter, Andrea, would be sensationally exposed, and Munro's moral turpitude and literary legacy called into question and excoriated.

I sat outside on the 18th-floor balcony at my nephew's apartment Sunday, writing about Munro and reading excerpts from Robert Thacker's (the academic authority on Alice Munro) 2005 biography, Alice Munro Writing Her Lives. I had designated this day to write about the Literary Trail. I absentmindedly picked up my cell phone when I went inside to escape the blinding sun. I started reading a tweet by American writer and novelist Joyce Carol Oates and a lengthier tweet by American novelist and journalist Joyce Manard. It felt like someone had repeatedly kicked me in the stomach. The feeling persists. I tossed and turned Sunday night and was dizzy with shock, disappointment and confusion over the previously unacknowledged culpability of Skinner's parents, Jim and Alice Munro.

I immediately and intuitively believed Skinner's accusations and was overcome by her courage and tenacity to bring them to light. I dug deep into my feelings and biases and considered how to react and respond emotionally to others who have been profoundly wounded, triggered and affected by these revelations. I know from other people who are close to me that living with the emotional aftermath of sexual abuse and incest is traumatizing enough. Unfortunately, many survivors open up about their abuse, only to find that family members' reactions toward them are unbearably egregious, if not more so, than the initial trauma.

Over these last few days, I have asked myself whether moral failing should erase a dedicated lifetime of writing. I have no intention of jumping on the moral high ground that is intent on vilifying and erasing Munro's literary legacy. There is bound to be more revelations that will add additional context to this story. I have wondered how many people were complicit in keeping this story suppressed, and what was their motivation other than financial? Has Douglas Gibson, Munro’s longtime publisher, editor and confidant spoken out?

I have heard from other trusted writers that Skinner had tried to have this story told, but it was just now, after Munro's death, that people were interested in publishing it.

As my friend Penn Kemp commented, “The stories remain. Read them in a new light.”-BL

Excerpts from Andrea Skinner's Essay

This past Sunday, Munro's youngest daughter, Andrea Skinner, revealed in an op-ed on the front page of the Toronto Star that her stepfather, Gerry Fremlin, had molested her when she was 9, and she told her mother about it when she was 25. Munro chooses to stay with her husband after briefly leaving him and flying to her Comox, British Columbia residence. Skinner disclosed that Fremlin repeatedly exposed himself to her and made sexually explicit statements to her until her adolescence. Fremlin pled guilty to sexual assault in 2005 and received a suspended sentence and probation.

Skinner divulged that when she was in her 20s, Munro expressed sympathy for a character in a short story who died by suicide after being sexually abused by her stepfather. It was after this that Skinner wrote to Munro about the abuse she had suffered. In a letter, she told her mother what Fremlin had done to her. Rather than responding with empathy and compassion, Skinner said, Munro "reacted exactly as I had feared she would as if she had learned of an infidelity."

Fremlin wrote letters to the family, Skinner said, in which he admitted to the abuse but blamed it on Skinner. When she went to the police in 2005, she took these letters. "He described my 9-year-old self as a 'homewrecker,'" Skinner wrote. According to Skinner's essay and the article in The Toronto Star, Fremlin accused her of invading his bedroom "for sexual adventure" in one of the letters he wrote to the family.

"If the worst comes to worst I intend to go public," Fremlin wrote, according to Skinner's essay. "I will make available for publication a number of photographs, notably some taken at my cabin near Ottawa which are extremely eloquent … one of Andrea in my underwear shorts."

Despite all this, Skinner wrote, Munro went back to Fremlin and remained with him for the rest of his life. "She said that she had been 'told too late,'" Skinner wrote, "she loved him too much and that our misogynistic culture was to blame if I expected her to deny her own needs, sacrifice for her children, and make up for the failings of men. She was adamant that whatever had happened was between me and my stepfather. It had nothing to do with her."

Skinner states that she and Munro became estranged decades later when, while pregnant with twins, she told her mother that Fremlin could not be around her children. "And then she just coldly told me that it would be a terrible inconvenience for her (because she didn't drive)." Skinner did not feel the need to reconcile with Munro after that incident.

"I made no demands on myself to mend things, or forgive her. I grieved the loss of her, and that was an important part of my healing," she wrote.

By coming forward with her reality, Skinner is working toward the same goal she stated about reporting Fremlin's abuse to the authorities in the first place: "I also wanted this story, my story, to become part of the stories people tell about my mother. I never wanted to see another interview, biography, or event that didn't wrestle with the reality of what had happened to me, and with the fact that my mother, confronted with the truth of what had happened, chose to stay with, and protect, my abuser."

Now, after Munro's death, Skinner and her siblings have reconciled. We are told that Munro's children worry about this revelation's impact on her legacy, but the need to air the truth is greater. "I still feel she's such a great writer—she deserved the Nobel," said Sheila Munro, that eldest daughter. "She devoted her life to it and manifested this amazing talent and imagination. And that's all, really, she wanted to do in her life. Get those stories down and get them out."

The press has swiftly and brutally condemned Munro's behaviour towards her daughter. Many are calling for Munro's "cancellation."

"I want so much for my personal story to focus on patterns of silencing, the tendency to do that in families and societies," Sheila said. "I just really hope that this story isn't about celebrities behaving badly ... I hope that ... even if someone goes to this story for the entertainment value, they come away with something that applies to their own family."

“A turning point came when I read an interview with my mother, Alice Munro, in The New York Times, in which she described my stepfather as a gallant figure in her life. For three weeks I was too sick to move, and hardly left my bed. I had long felt inconsequential to my mother, but now she seemed to be erasing me.

I wanted to speak out for the truth. I went to the police and told them of my “historical” abuse, and showed them my stepfather’s letters. They pressed charges. I’d had to confront my shame (and other people’s), which was telling me I was being vindictive, destructive, cruel. For so long I’d been telling myself that holding my pain alone had at least helped other family members in important ways, and that the greatest good for the greatest number was, after all, the greatest good. Now, I was claiming my right to a full life, taking the burden of abuse and handing it back to my stepfather. Was I worth it? Was I even capable of a “full life”? How could I knowingly make any other human suffer only to maybe feel better? I answered these questions by imagining one of my children in this situation. Wow, that was easy. I was able to go ahead with it.

My stepfather was convicted of sexual assault, and got two years’ probation. I was satisfied. I hadn’t wanted to punish him, and I believed he was too old to hurt anyone else. What I wanted was some record of the truth, in a context that asserted I had not deserved it. I needed that. But victories such as these still hurt; they just hurt less than doing nothing.” - Andrea Robin Skinner

The Alice Munro Festival of the Short Story posted:

Dear friends: Some of you may have already seen the recently released essay by Alice Munro's daughter, Andrea Robin Skinner. In that essay, Ms.Skinner shares that her stepfather sexually abused her. We are shocked and saddened by what has come to light about Alice Munro's private family life. The festival needs to consider the impact this has on its future programming. This is her story as Ms. Skinner continues her deeply personal and challenging healing journey. As such, the festival will have no further comments.

The stories remain, read in a new light. Thank you for sharing this, dear Bryan.

I can only begin to imagine the pain this has brought to you. As always,you’ve conveyed your thoughts in an authentic and heartfelt manner.Beautifully written.