“We can’t resist this rifling around in the past, sifting the untrustworthy evidence, linking stray names and questionable dates and anecdotes together, hanging on to threads, insisting on being joined to dead people and therefore to life.”

Alice Munro - “Messenger”

“If you’re a writer, you’re sort of spending your life trying to figure things out, and you put your figurings on paper, and other people read them. It’s a very odd thing, really.”

Alice Munro- Interview (2013)

After experiencing some significant challenges over the past few months, I have had little opportunity to organize my writing time on Substack. Nevertheless, I have been determined to visit Clinton and Wingham twice in the last few weeks to honour Alice Munro and offer some random thoughts about the writer who has influenced me the most.

Munro, a beloved writer and masterful practitioner of short stories (only rivalled by Mavis Gallant) passed away on May 12th, 2024, at 92, after battling dementia for the last decade.

During my visits to Huron County, I had the chance to speak with locals about Munro and her enduring legacy. On one visit to Alice Munro Literary Garden, a tiny oasis dedicated to Munro in downtown Wingham, we stopped to talk to Vickie and her 25-year-old green-winged macaw, Casey.

I often visit Munro's hometown of Wingham in the summer and well into the fall to buy produce from nearby Mennonite farmers in the Wroxeter-Gorrie area, a practice I've maintained for over twenty years. In the summer, on my way to Sauble Beach, I frequently stop in Clinton, Blyth, Wroxeter, Wingham, and Belgrave, and occasionally in Bayfield and Goderich.

I've been eager to establish a literary trail to honour her short stories, which are deeply rooted in the accuracy and resonance of the Huron County landscape. I plan on pinpointing the exact "Alice Munro Country" locations where many of her fictional and autobiographical literary scenes are set.

Munro is internationally renowned and has won the Governor General's Literary Award three times. She has also won the Giller Prize, the Man Booker International Prize, and, most notably, the Nobel Prize for literature in 2013. Munro had a literary relationship with The New Yorker spanning decades with more than 60 of her short stories published. She is one of Canada's most beloved writers. I have been a devotee of her essays and short stories for nearly four decades.

After several unsuccessful attempts (no GPS) I recently tracked down Munro's former home, a white cottage on a large corner lot in Clinton, the family home of her second husband, Gerald Fremlin. Part of the original double lot, which has been described as an eccentric garden has been sold off to make way for two new houses next to the railway tracks.

Munro’s red brick childhood home with distinctive contrasting decorative polychrome brickwork in Wingham is secluded at the end of a long river road. It is the last house in town, with a farmer's field on one side and the Maitland River on another. There are many newly built homes nestled along the road facing the river.

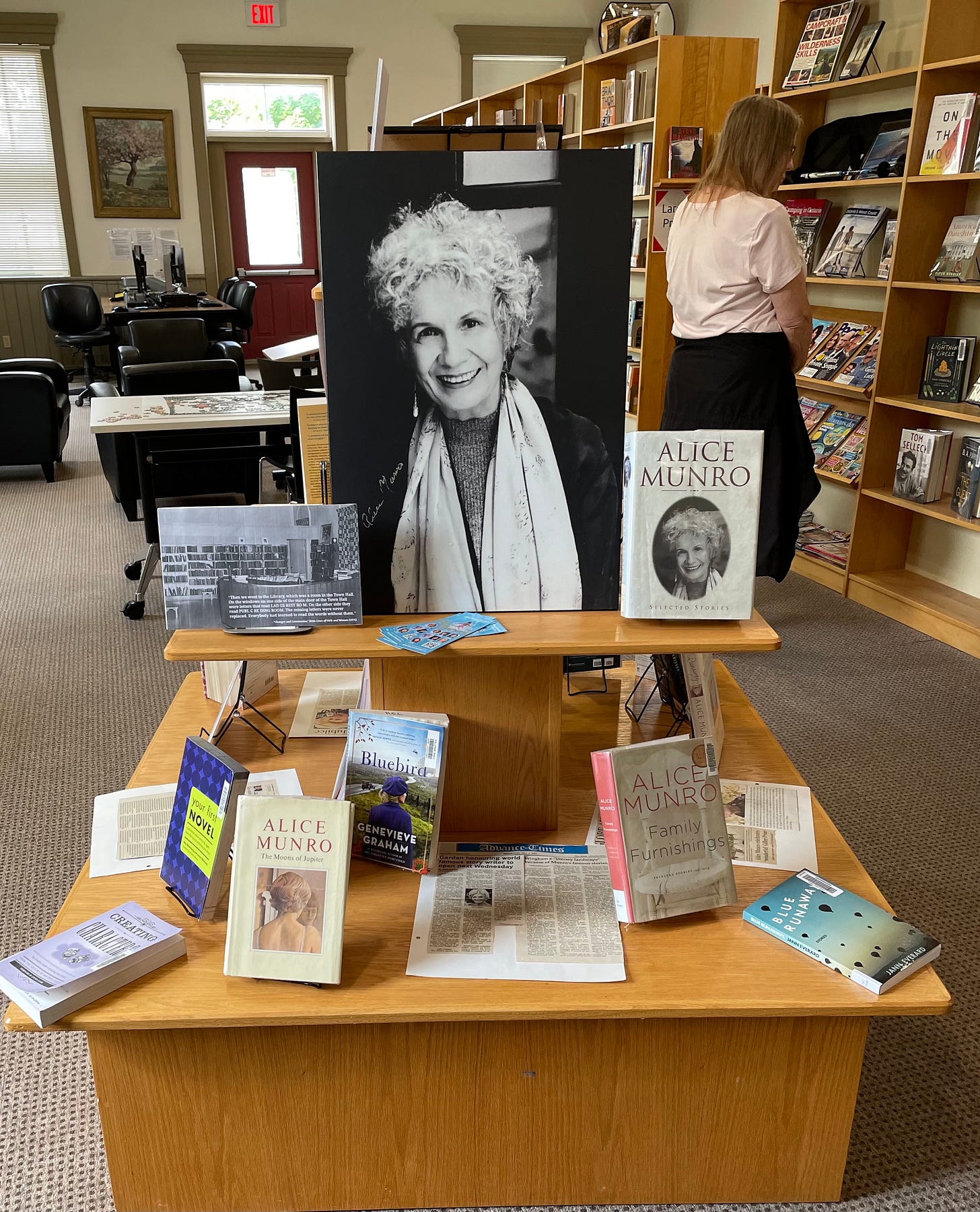

On my last visit, I returned to the Alice Munro Literary Garden. I went to see the Alice Munro exhibit at the Alice Munro Library. I spoke with Branch Manager Trina Huffman about library visitors interested in Alice Munro. We talked briefly about my plans to develop an Alice Munro Literary Trail. Incidentally, there is already a self-guided recreational tour from Alice Munro's published writings produced by the Township of North Huron. This is also the week of the annual Alice Munro Festival of the Short Story. Wingham Homecoming is June 27 to July 1st. There are planned Alice Munro-related festivities at the Alice Munro Library.

Often referred to as Alice Munro Country, the writer's birthplace and the subject of her prose, this neck of the woods is rural and conservative. It has ingrained farming practices, stalwart beliefs, and once stultifying communities are enjoying a renaissance. In Munro's short stories, some fictional towns are Jubilee, Hanratty, and Walley.

Our paths crossed many times, although I never met Alice Munro. Watching interviews and rereading her volumes of short stories has been like reminiscing with a longstanding and trusted friend, the shared unexpected insights, macabre revelations and universal insights.

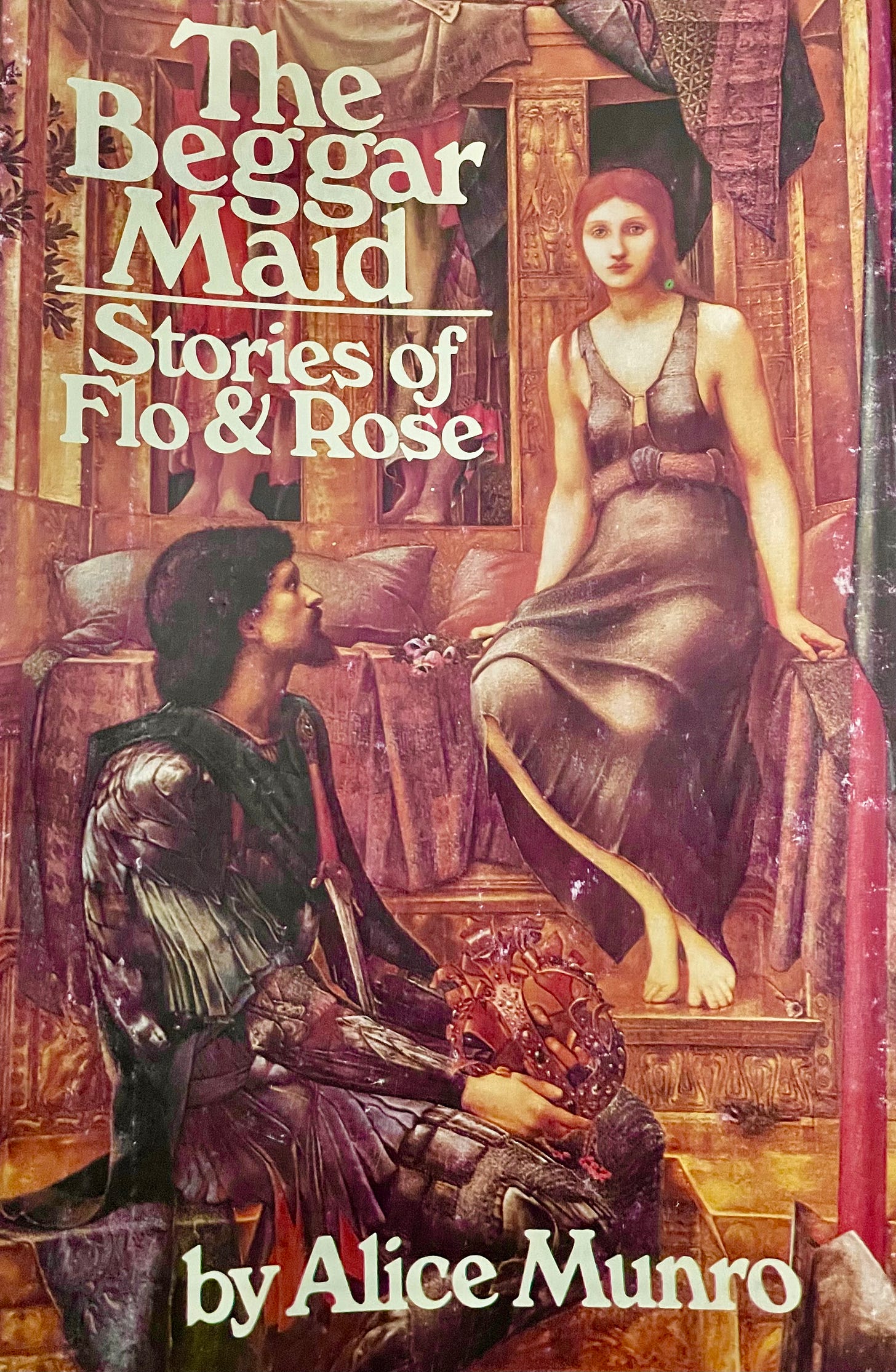

My earliest memories of Munro are from the late 1970s when my friend Donna Rowsell (Gary’s sister) worked at the independent bookstore, The Country Mouse, on Richmond Street in London, Ontario. The bookstore, operated by two staunch feminist women and life partners, often hosted local women authors such as Munro and Margaret Atwood. I remember reading The Beggar Maid. Several stories, such as Half a Grapefruit, Royal Beatings and Privilege, stood out.

I remember hearing Munro was a Writer in Residence at Western University in 1974.

Around 1980, I had a small Antiques shop a few doors from The Country Mouse Bookstore. I took a more serious interest in Canadian literature, concise stories and essays, and the writings of Alice Munro, Mavis Gallant, Margaret Atwood, Margaret Laurence and later Carol Shields and Bonnie Burnard.

In the early 1980s, I returned to Toronto. I lived in an industrial warehouse converted into a mixed-use space just south of Queen Street near Spadina. This type of rental was a grey area of the law, if not illegal. Still, it attracted emerging artists and other struggling creatives due to the space, high ceilings with anaglyptic tiles, and relative affordability. There needed to be a kitchen or proper amenities, but there was a shared washroom. The building had an ancient freight elevator off the loading dock that provided access to my living space/loft through a service corridor. I would have breakfast every morning at Rooneem's, an Estonian bakery at the corner of Queen Street and Dennison, before taking the Spadina subway north to Bloor and Bay Streets and my job at Le Trou Normand Restaurant in Yorkville. Rooneems' Bakery, located a block from the Writer's Union (a pivotal and necessary advance in the professionalization of writing in Canada) and close to artist Charles Pachter's studio and gallery restaurant Gracie's, provided a comfortable, quiet locale for several notables who could spend time there without unwanted attention. Aino Rooneem recalls writers Alice Munro, Margaret Attwood, Barbara Frum, and Barbara Amiel frequenting the restaurant.

In her story, Bardon Bus, Munro describes sitting in Rooneem's where she can watch the street, "drinking coffee, with people coming and going, eating and drinking, buying cakes, and speaking Spanish, Portuguese, Chinese and other languages that you can identify."

It's been nearly forty years since I became enamoured of Bayfield a charming historic village located on the shores of Lake Huron.

Restauranteur/entrepreneur Tania Auger of Sarnia's Lola Lounge had asked me to join her in opening the Shark Inn (formerly the Ritz Hotel—now the location of the rebuilt Virtual High School—on the main street across from The Little Inn) in 1987.

I was acutely aware of Munro's presence in Bayfield and its proximity to Clinton. She dined across the street at The Little Inn, The Red Pump, or walked along the broad, pedestrian-friendly Main Street with its pea gravel pathways, majestic willow trees, historic yellow brick, and clapboard buildings. In many ways, the village nestled on the precipice of the sandy eastern shore of Lake Huron remains much as it was four decades ago and in some of Munro's timeless short stories. Years later, she was often spotted unobtrusively leafing through the pages of books at the Village Bookshop. She was private and self-effacing to some extent but enjoyed having her writing acknowledged and recognized.

There were often sightings of Alice Munro at Bartliff's Bakery (the 132-year-old iconic bakery that is a frequent stop of mine) or at the Clinton post office. Baileys Restaurant in Goderich, which Munro is where New York, Toronto and Los Angeles reporters interviewed the prodigious award-winning Huron County writer hailed North America's best fiction writer. Her long-time editor and publisher, Doug Gibson, once advised, "If the publicity-shy Munro agrees to talk, you should invite her to lunch at Bailey's in Goderich. He said to reserve ahead and ensure her table is ready. It's where she is most comfortable, where other diners know her, and the county code enough not to make a fuss." The Benmiller Inn, midway between the towns of Clinton and Goderich, was another hideaway to meet with journalists.

On the surface, Munro's writing focused on the allegiances of small-town respectability borne of thrift, alienation and the undemonstrative Irish-Scottish Presbyterian morality that thrived in the hardscrabble region of Huron County. Munro's stories concentrate on stern Protestant judgements with ambiguous themes, hypocrisy and submerged subtexts of dour morality, repressed sexuality, infidelity and prohibition.

Munro intersperses some of her writing with stories about the Scottish work ethic, a secularized force specific to Scotland, influenced by a zealous Calvinistic religious heritage, Sabbath observance, tight-fisted frugality, temperance, and education, which her writing lays bare. Munro's characters often flee rigorous fundamental strictures of conformity, convention, and a calibrated social class hierarchy.

These once hermetic small towns, hamlets and the surrounding Huron County countryside to the east of Lake Huron, with great expanses of Ontario farmland bisected by concessions intersecting at precise right angles, are dotted by a patchwork of crop fields, redbrick or rough-hewn stone farmhouses with rows of resilient windbreak trees and the occasional maple leaf flag flying to denote unalloyed patriotism.

Munro explained that they moved to Clinton in the late 1970s to care for her second husband, Gerald Fremlin's elderly mother, who was not exactly ill but frail after her husband died. They never saw any point in living elsewhere. Munro grew up further up Highway 4 in Wingham, where her father raised turkeys and silver foxes at the farthest edge of town on a meandering river road that becomes a dead-end.

The preview of Munro's fiction reflects small-town rural communities where aspiration and assertiveness are looked down on, especially in women. Ambitions are covert, and there's a pervasive perception and tension that everyone knows, or thinks they know, everyone else's business. The town's collective point of view is distilled in social attitudes and becomes a character in itself.

Old-order Mennonites have taken over the Scots-Irish farms east of Wingham and around Wroxeter, Belmore and Gorrie. After years of travelling concessions and scouting dirt back roads in north Huron County, about fifteen years ago, we began to notice a renewed prevalence of hand-painted signs and newly erected farmgate stalls at the end of long unpaved laneways throughout the countryside. The modest chalkboards and hand-crafted wooden signs announce: free run eggs, horseradish, honey, maple syrup, sauerkraut, rhubarb, strawberries, seasonal vegetables and fruit, fresh-cut bouquets, baking and "No Sunday Sales." Often, there's no one there to receive you, just a wooden box or a locked drawer to drop your money. It is called the honour system.

I recently purchased a first edition American copy of The Beggar Maid. Stories like Half a Grapefruit are autobiographical in feeling and sentiment, but not necessarily so. Many of these stories had a surprising and relatable affinity with my partially rural teenage years when I lived by Rice Lake and the villages of Westwood, Hastings, and Norwood in central Ontario and later living just over an hour and a half away from Huron County by car for the last forty years.

The story, Half A Grapefruit, starts in a high school classroom, where the young and optimistic teacher has asked each student to share what they had for breakfast to see if they were keeping Canada's Food Rules. The classroom is divided, with aloof, waffle-eating and coffee-drinking towners from the town proper sitting on one side and less privileged rural children on the other. Previous stories in The Beggar Maid include "Royal Beatings" and "Privilege," highlighting Rose's shame about her family’s circumstances. Despite residing in West Hanratty, the river's underprivileged side, she feels her family doesn't fit in. Rose attaches herself at the end of a row of town kids in the classroom, trying to align herself with "knowledgeable possessors of breakfast nooks,” placing her in a position of vulnerability. As the town kids exaggerate their hearty breakfasts and the rural students disclose more rudimentary and meagre breakfasts, Rose decides to differentiate herself from everyone else. She fibs and claims she ate half a grapefruit for breakfast. Momentarily, she is pleased by her ingenuity, but her fabrication backfires. The kids can tell Rose is lying (even though they know how to prevaricate themselves.) The town kids can see through her pretensions, and as a result, Rose becomes even more ostracized when they mockingly shout or whisper "half-a-grapefruit" at her from an alley, under a bridge or a dark window, now and again for years to come.

https://www.huroncountymuseum.ca/alice-munro-local-resources-for-teachers-students/

“It was a common idea not to try too much, never to think you were smart. That was another image that was very popular. Oh, so you think you are smart. And to do any writing you have to think you’re smart, for quite a while…”

Alice Munro, In Her Own Words: 2013 Nobel Prize in Literature

A lovely tribute. So looking forward to exploring Alice Munro country and sharing stories!

Alice Munro was obviously brilliant. I've watched and re-watched many interviews with her. I find her writing to be so brave, so honest and her descriptions stay with the reader. Wonderful to hear how she has impacted your own life and I enjoyed reading the little details about where you ate breakfast at the time etc. And a "trail" is such a good idea!