Until mid-July 2024, with semi-retirement in sight, I had been working diligently on curating an experiential Alice Munro Literary Trail that I planned to launch in the spring of 2025. I have spent several years developing and curating a series of guided and self-guided culinary experiences and experiential culinary trails. In 2020, I was awarded the Ontario Culinary Experience Award for my company, Forest City Culinary Experiences, for offering curated and customizable culinary experiences and partnering with other community organizations to develop sustainable experiences for followers and culinary enthusiasts. In 2023, I co-developed a Scratch Bakery and Patisserie Trail for Downtown London's BIA. These successes gave me the inspiration for an Alice Munro Literary Trail.

My objective for the Alice Munro Literary Trail is to highlight and identify Munro's short stories by showcasing the precise southwestern Ontario settings and regional landscapes where many of her literary scenes found inspiration or took place. The trail would also include historical locations in "Alice Munro Country," such as the Laidlaw family home in Wingham, her former house (husband Gerald Fremlin's family home) in Clinton, the Alice Munro Library, the Alice Munro Literary Garden in Wingham and the monument honouring Munro and her literary achievements outside the Clinton Library.

In her stories, the towns often take on whimsical, fictional names like Jubilee, Tuppertown, Walley, Tiplady, Mock Hill, or Wawanosh, evoking a sense of charm and imagination. Yet, regardless of these made-up titles, the authentic essence of places like Wingham, Clinton, Goderich, Blyth, and Bayfield shines through with striking clarity. Through Munro's distinctive and richly detailed depictions, readers can easily discern the true character and landscape of the region, woven into her narratives with a masterful touch.

Many of my readers are likely familiar with Munro's literary oeuvre. Still, for those who are not, Munro, a Wingham native in rural southwestern Ontario native, died on May 13, 2024, at 92. Munro had progressive memory loss and cognitive decline for over a decade before her death. She was the most respected and lauded Canadian contemporary short story writer (alongside another of my favourites, Mavis Gallant.) I felt a strong kinship with Munro and her writing, bordering on idolatry as do many of my contemporaries.

Southwestern Ontario is fertile literary ground, giving rise and perspective to writers Joan Barfoot, Bonnie Burnard, Marian Engel, Robertson Davies, Graeme Gibson, James Reaney, Penn Kemp and, to some extent, Emma Donohuge, to name various others.

Munro, a national treasure, was awarded the Booker Prize and, in 2013, the Nobel Prize for Literature. Her eldest daughter, Sheila, accepted the prize due to her mother's developing illness and fragility.

Munro's prolific essays, many published in the New Yorker (over 50 at last count), established Munro's international reputation as a master of short stories and prose fiction and has been compared to writers from Thomas Hardy and James Joyce to Willa Cather. She is “our Chekhov, our Flaubert.” Many consider her short stories among the most critical, rich in subplots, movement in time and ancillary characters.

Munro grew up outside Wingham, Ontario, with a long walk to and from school. To pass the time, she created stories and started putting them on paper when she was 10 or 11. She went on to study English and journalism at Western University before moving to British Columbia when she was 20. Western University has long publicized its association with Munro and, since 2018, has employed an Alice Munro Chair in Creativity. In the months following Alice Munro's death in May, her youngest daughter, Andrea Skinner, revealed a troubling family history of sexual abuse by her mother's partner, Gerald Fremlin. Despite being aware of the abuse, Munro chose to stay with Fremlin, leading to her estrangement from Andrea. Western University paused the endowed chair program that bears her name over revelations Munro protected her husband after learning he had sexually abused her daughter.

In June 2024, I visited Munro's former home (her second husband Gerald Fremlin's family home) and the iconic Bartliff's Bakery (a Huron County tradition since 1902 and a favourite haunt of Munro's) in Clinton numerous times in the past thirty-five years on my way to source quality Mennonite ingredients and produce just outside Wingham for restaurants I operate or on my way to a friend's cottage in Sauble Beach. I initially became aware of Munro's presence in Clinton when I was sourcing bakery items from Bartliffs for a small hotel I operated in Bayfield in 1987.

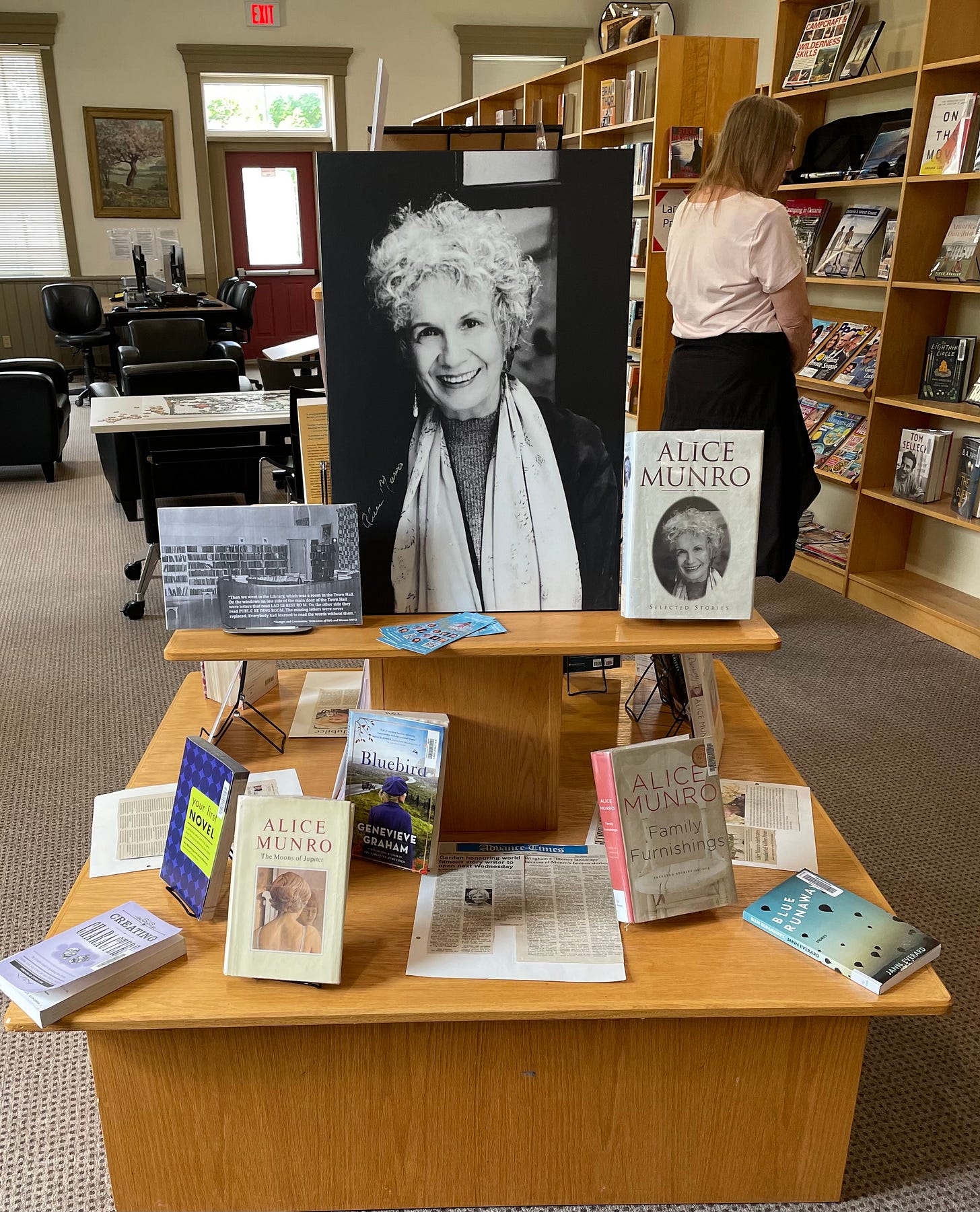

I have travelled the long road Munro walked to school, visited and photographed the exterior of her childhood home in Wingham, and, on multiple occasions, the Alice Munro Literary Garden and the Alice Munro Library. The head librarian at the Alice Munro Library, Trina Huffman, told me that unidentified family members had been to visit the Alice Munro Library to see the original exhibit a few days earlier when I visited in early June.

Since revealing the news about Alice Munro's daughter in the Toronto Star, the Huron County Library has received numerous inquiries from the media and the public about whether there are plans to change the name of the Wingham Branch, currently named after Munro. "We understand the community's interest and concern regarding this matter; however, no decisions will be made at this time. We believe this is a serious and complex situation that requires careful, thoughtful consideration."

The Huron County Library has committed to a listening period without taking action for at least six months to address this. All comments and concerns will be documented and presented to the Huron County Library Board at their first meeting in 2025. At that meeting, the Board will determine if further consultation is needed and what actions should be taken, if any."

This summer, I spoke with out-of-towners visiting the Literary Gardens about her short stories and with Wingham locals about Munro on the street. An introduction to a communicative 25-year-old green-winged macaw named Casey, who sat on my arm, and the extroverted owner had much to say about Munro being a controversial figure in town.

I visited the new Alice Munro exhibit at the Alice Munro Library for the Wingham Homecoming 2024. On another occasion, we were greeted by an elderly, friendly farm dog when we stopped by the 5-acre pastoral Blyth Union Cemetery to locate Fremlin's headstone. I remember reading that Munro planned her internment alongside him. The crowded graveyard site has a mausoleum, chapel and a garden shed. Fremlin's non-descript headstone did not feel fitting for a person of Munro's stature. I would later read that Munro had changed her mind about her burial site after Fremlin died. She told her daughter, Sheila, "I do not want to be buried next to that man."

Little did I know what lay ahead. Fremlin's sexual abuse of his step-daughter, Andrea, would be sensationally exposed after being repressed for decades, and Munro's moral turpitude and literary legacy would be called into question and excoriated by the media.

On the July weekend that the revelations about Andrea Skinner broke in the Toronto Star, I was sitting outside on the 18th-floor balcony at my nephew's apartment in downtown London, Ontario, writing about Munro and reading excerpts from Robert Thacker's (an academic authority on Alice Munro) 2005 biography, Alice Munro Writing Her Lives. I had designated this day to write about and further develop the Alice Munro Literary Trail. Absentmindedly, I picked up my cell phone when I went inside to escape the blinding sun. I began reading a tweet by American writer and novelist Joyce Carol Oates and a lengthier tweet by American novelist and journalist Joyce Manard. It felt like someone had repeatedly kicked me in the stomach. Now when I read articles about the previously unacknowledged culpability of Skinner's parents, Jim and Alice Munro the feeling returns.

Immediately and intuitively I believed Skinner's accusations and was overcome by her courage and tenacity to bring them to light. I dug deep into my feelings and biases and considered how to react and respond emotionally to those profoundly wounded, triggered and affected by these revelations. I know from other people who are close to me that living with the emotional aftermath of sexual abuse is a lifelong traumatizing experience.

Over these last few months, I have asked myself whether ethical failing should erase a dedicated lifetime of writing. The answer is no. I have no intention of jumping on the moral high ground that is intent on vilifying and erasing Munro's literary legacy. More scandalous revelations have added additional context to this story. Most notable is a recent article in the New Yorker, Rachel Aviv's "Alice Munro's Passive Voice," which delves into the conflicting themes of prerogative and disenfranchisement in Munro's life and oeuvre, highlighting her choices' profound effects on her daughter and others. Aviv interviews Andrea and her sisters Sheila and Jenny and carefully and comprehensively examines Munro's letters and short stories to uncover truths about the celebrated author and the limits of her art and legacy.

Sheila and Jenny have found a new cemetery in Wingham, where Munro's Alice's ashes will be interred when the time is right for the family. I have resumed my work on the Alice Munro Literary Trail. Heartbreakingly, Andrea has finally been heard.

I too am a long time reader and admirer of Alice Munro and Mavis Gallant. I love a good short story. My mother is from a big family from Staffa so I know the area well. The feeling of being kicked in the stomach was a very apt description. I hope to learn about the trail you have been putting together so I can experience it.

There have been heated discussions around many dinner tables in Canada regarding sexual abuse, even to the point of whether Munro should be read at all. I couldn't agree more with you, Bryan. Many of us also felt that kick.