Photo Bryan Parker Lavery

Cultural Appropriation, Unconscious Gastronomic Bias and Restaurant Writing

I last wrote extensively about food or restaurants before the pandemic. Instead, I turned my hand to essays, short stories and memoirs. Before the Covid-19 pandemic, among other things, I was a principal freelance writer and food editor for Eatdrink magazine for twelve years, helping to shape the magazine under my byline and behind the scenes. During this period, I wrote content for several other tourism guides and magazine articles, sometimes requiring me to go on FAM trips—meaning destination familiarization trips with food writers and influencers. In those cases, I disclosed my affiliations. I also had a storied thirty-five-year career as a restaurateur and chef.

My restaurant writing remuneration was based on per article or column, and I was not given an expense account for dining out or reimbursed for my expenses. Despite it being unsustainable, it would not have occurred to me to not pay my own way, having been in the restaurant business for so many years. I was deeply committed to this work, and it would have been a peripatetic existence if I didn't have other passion projects. Also, paying your way is imperative because it helps keep your recommendations honest and truthful. Influencers and bloggers must disclose to their followers whether they receive money, commissions, free products, services, discounts, gifts, or free trips.

At the onset of my food writing career, I was a weekly food columnist for the London Free Press twenty-five years ago while running my restaurant Murano. I have been championing the London, Ontario, culinary scene for many years and have worked independently and collaboratively to help shape London, Ontario's culinary identity. Sometimes I get my hackles up when I read poorly researched food and drink articles where image, generalization and misrepresentation are the base standards.

As I have often said, good food media are necessary members of the culinary community. Like any thoughtful patron, we want to bring appreciation and sensibility to the table, but the food media's mission goes beyond that. We must pass our unbiased impressions on to the readers while alerting the dining public to the diversity of choice on the culinary scene without omissions, airbrushing and white lies. Good reporting furnishes you with enough information and insight to make informed decisions while helping arbitrate eating-out standards. If you don't have good, vital food media whether you love or despise them—you don't have the same degree of interest, enthusiasm and accountability. It has always been clear that there is no way to have just one meal in a restaurant and give a fair and credible critique if you approach restaurant reviews with integrity. Three visits and ordering multiple items is the minimum requirement for restaurant reviewers.

In recent times, social media influencers have been lionized as a prominent subset of digital content creators defined by followers, distinctive brand personalities, and relationships with corporate and commercial sponsors to promote conspicuous consumption. Despite widespread contrast in influencer practices across platforms such as Instagram, YouTube, TikTok and Facebook, most influencers earn revenue by promoting branded goods, experiences and services to a large community of followers.

There is a constant need for social media influencers and food content creators to constantly feed on new ideas that give them fresh sound bites and street cred. No reader wants influencers or reviewers to pile unrestrained acclaim on every restaurateur, chef, brewery, distillery or travel destination. It's disingenuous, and it becomes obnoxious. The conceit that every meal is seminal is tiresome and implausible.

It makes me unhappy when I read columns by oblivious influencers who possess cursory knowledge but feel entitled to inflict unnecessary hyperbole on the rest of us. But what is worse is the influencers who phone it in because they need more of an understanding of a destination's culinary identity. How many meals can you eat, and how many restaurants can you review in two to three days?

The credible reviewer or influencer can't simply be a euphoric advocate, someone whose admiration for a restaurant or chef is reduced to innocuous platitudes. We need to remember a thoughtful and intelligent negative review has its merits. We do not need to airbrush everything to make it more palatable to readers. Honesty pays homage to serious chefs, restaurateurs and hoteliers who want to be critiqued fairly and objectively rather than showered with meaningless praise.

Food, identity and culture are bound together, and inadvertently insulting customs and cuisines you don't fully understand are offensive. Even a layman should meet specific journalistic standards when writing about food. Writers who have strong opinions in a given discipline or make sweeping statements — and many of us do — but don't have the broader knowledge or context that provides an argument with merit and weight are not credible spokespersons.

We don't need lists segregating the restaurant diaspora. We must avoid the idea that white and western are the base standard. Ubiquitous and arbitrary listicles are often used to fill a quota for representation. These types of lazy, arbitrary listicles are the worst despite the fact they have become ubiquitous.

We must remember that food and drink confer status and entitlement to the economically and culturally privileged, consequentially perpetuating social inequality, offensive stereotypes, and cultural appropriation at the hands of the white cultural monopoly.

A recent example of cultural appropriation is a talented, local Mexican cook and colleague who was recently asked to provide traditional Mexican recipes to her white male chef colleagues so they could cook a Mexican-themed Brewmasters Dinner for a collaborative event instead of hiring her for the event.

Privilege or the appearance of privilege underpins online content creation. It really is time to unsubscribe from these privileged media and influencer narratives that still validate and uphold colonial power dynamics and cultural appropriation.

The narrative of food and drink media is often used to position the reader as a traveller, white, Western, heterosexual, affluent, and educated. Why are there lines of distinction drawn? It is all cuisine and part of the culinary mosaic. Period.

Ethnic is a word that should have fallen by the wayside long ago. The vagueness of the term "ethnic" and the expectation that it doesn't apply equally to people and cuisines associated with Europe or white America should give everyone pause. It is subjective and doesn't make much sense. Ethnic to whom, or to what? The term ethnic is a catchall for non-white used to devalue immigrant cuisine, and its associated stereotypes are no longer acceptable. These double standards and cultural misrepresentations of cuisine are derogatory and insensitive.

The expectation of assigning lower prices for cultural foods such as tacos, masalas, injera, spring rolls, pupusas and dumplings undervalues those who cook the cuisine and their culinary heritage. One significant constraint for Indian, Mexican, African or Asian cuisine is that it is not deemed genuine if expensive. Until recently, immigrant cooks on the lower echelons of the social hierarchy were held captive by the insistence on cultural authenticity — (read cheap cuisine), and all that term implies. How a culture's cuisine is valued is often seen in relation to the status of those who cook it. And who gets to decide what "authentic" actually is?

There should be no distinction made between immigrant and non-immigrant cuisine. Like its people, what is considered Canadian cuisine is a wide-ranging mix of appropriated indigenous and immigrant cultures, traditions and tastes that have adapted to the people who have immigrated here and call this country home. At their best, authenticity and cultural exchange is the willingness to respect and value another culture's traditions.

Let's not forget that as the coronavirus spread worldwide, bigotry toward Asians, their cuisine and restaurants were not far behind, fueled by the news that COVID-19 first appeared in China, resulting in subsequent racist tropes and anti-Asian sentiments. I recently heard a similar trope perpetuated by a participant at lunch at a recent tourism conference.

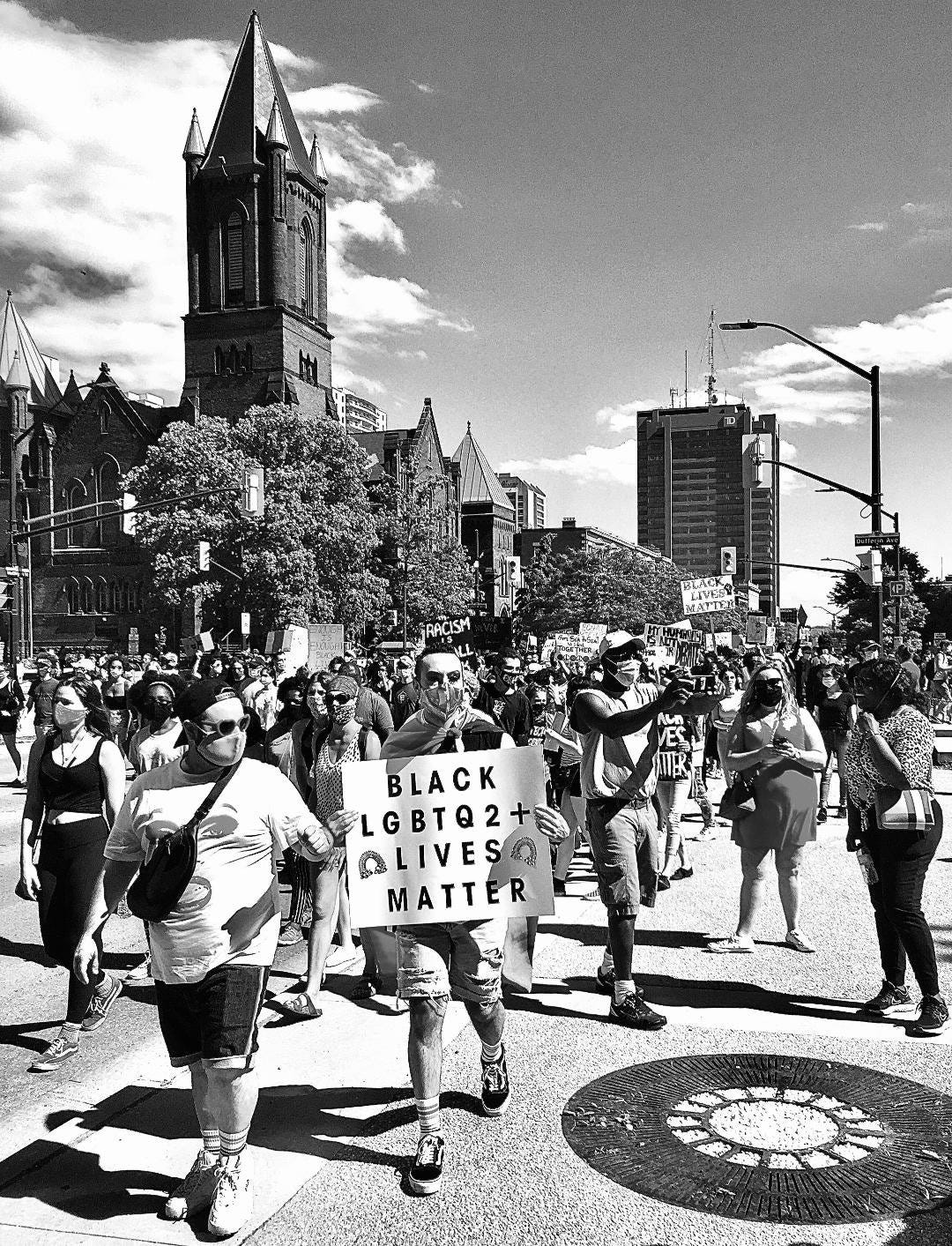

And well, we are at it; we need to embolden more inclusive voices of a diverse restaurant diaspora of immigrants, women, LBQTQ2S+( Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer or Questioning, and Two-Spirit) and BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and People of Colour) in our local food media. The white cultural monopoly should remember that the BIPOC population currently comprises 27% of Canadians that are also travellers and diners with eclectic tastes. We need to find different ways to write about the restaurant diaspora, immigrant chefs and food spaces that are much more equitable and inclusive. And speaking of inclusive, I was recently told that I was selected to sit on a board, and it was implied that my primary credential was that I identified as Gay. It was suggested that I was filling mandates for addressing the under-representation of diversity and inclusion. We still have such a long way to go.

-BL

What incisive commentary from a storied chef and writer!