Catherine Bowie’s mother once told me Somewhere Over the Rainbow, written for the film The Wizard of Oz, was her favourite song. I was in my early thirties and had never heard the song. I put it down to the fact that my mother did not like Judy Garland.

Thirty years ago, Catherine was shot and killed by her semi-estranged husband. I had been living in Southampton, England, for five months, and that February, Southampton was dank and experiencing constant cruel cloud cover. I did not have a telephone, and I recall standing inside a red telephone kiosk, the rain pouring outside and talking to my mother long distance in London, Ontario. I remember counting eighteen equal-sized panes of glass arranged in six rows of three. Isolating homesickness had over taken me and it was just before nightfall and abruptly everything pitched to black. When my mother repeated the horrifying news and sickening specifics my friend Ben gave her about Catherine's murder, I was convulsed in pain and could not absorb the full magnitude of what I was hearing. Multiple times I asked my mother to repeat herself. The tragedy was incomprehensible. On the cold concrete floor of that telephone booth, I sat down and wept in desolation.

Thus began a period of profound spiritual devastation, disengagement and emptiness. The unrelenting shock waves and the survivor's guilt lasted several weeks, then months and years. Catherine used the phrase "dark night of the soul" to refer to spiritual bankruptcy, the absence of belief, and, more precisely, confronting her demons. Ironically, fate laid it bare before me. Her murder did not make sense. The universe did not make sense. Thirty years later there are still no answers.

Illogical and self-absorbed, I questioned whether I had been an unwitting enabler in the destructive behavioural patterns forming cracks in Catherine and George's marriage, even though they lived in Stratford and I in London, Ontario. As a recovering adult child of an alcoholic, I was beyond believing if I didn't help, the outcome for everyone involved would be far worse. Looking for unassailable answers, I had stopped drinking and had diligently attended AA meetings for a year.

Still, my mind demanded information and answers that were too great to process and store. My brother, Gary, was seeing a psychologist due to his recent break-up with his partner. The psychologist told my brother I would not recover until I could picture the bloody crime scene in my mind's eye. His remarks couldn't have been less helpful. It drove me to speak with the truculent pastor at the Metropolitan Community Church in Southampton, embroiled in a liturgical drama that gave an air of impotence to the awkward words of comfort he provided me.

Catherine asked me to intervene and speak with George the previous summer about their deteriorating relationship. She wanted a separation, and George was resistant. Catherine invited me to visit them on the Labour Day weekend at George’s lakeside family cottage in Grand Bend. I had sold my house and was leaving for England soon to meet up with my brother, Gary, and I had run out of time. There were too many last minute details to attend to. I found it curious when she did not answer the letters I mailed when I arrived in England. It was uncharacteristic.

Catherine was an only child. She was reared in suburban Oakridge with mature trees, quiet streets, and 1950s-era large split-level single detached homes. Catherine did not have siblings to protect her and help fight her battles, which made her self-sufficient and independent. She was outgoing and seemed to be the opposite of the only-child syndrome.

After her death, I endeavored to keep Catherine's memory alive. I often thought about the adage, there are two deaths, the actual death and the last time you are spoken about. There were extenuating circumstances while her parents were living, and of course, there was Catherine's estranged husband, George's, family to consider. I wrote to Catherine’s mother, Margaret, but she was unable to respond. We crossed paths several times but she kept her distance.

I met George’s sister Dorey, when Catherine and I were original hires at the Keg. In the mid-1980s, Dorey and I were both managing restaurants in Toronto's Yorkville, she was at the Bellair Café on Cumberland and I was at Le Trou Normand on Yorkville Avenue a block apart. Our paths have intersected for the last fifty years, personally and professionally. More recently, I had hoped that Dorey, an experienced consummate professional, would come to work with me. The pandemic made it problematic. We promised to keep in touch.

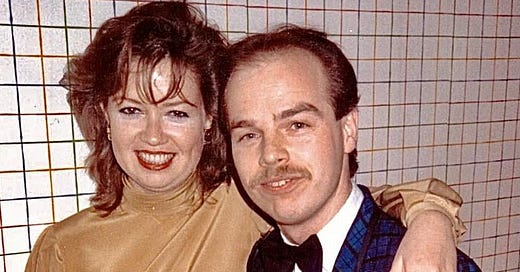

Catherine was kind. If I could only choose one definitive word to describe her, that would be it. She was a warm person, a con-conformist and free-spirit. She had a well-developed sense of the bizarre. She used words like Felliniesque, outré, kabuki and draconian to describe what she perceived as eccentrics, misfits, peculiar situations or patriarchal attitudes. Catherine possessed a sunny disposition despite her offbeat humour and wry, well-wielded witticisms. She was caring and went out of her way to extend that kindness to strangers on the street. Catherine had fair skin and blonde hair, and sometimes she wore classic dark red lipstick that would make her features pop. The last photograph I have of Catherine was sent to me by her mother after her death. Catherine hair is darker, she is wearing a scooped neck ocelot print dress, large gold hoop earrings, Mexican silver necklace and a trio of yellow Bakelite bangles. She has wide smile revealing her perfect white teeth and her eyes appear to be twinkling. She looks happy.

She liked to wear turquoise and calming pink, yellow and periwinkle pastels. Catherine had an artist's sensibility, was talented, and enjoyed sketching. She collected mass-produced kitschy religious iconography. The more sentimental the better.

I initially met Catherine while I was working at the Keg in 1973. She was exceedingly engaging and thoughtful, and striking. We struck up a friendship.

She did not show up for a lunch shift after a raucous late night staff party, and the management unceremoniously fired her. She was pragmatic, took it in stride and moved to Toronto. I remember Catherine telling me that she was not really cut out to wait on tables and wanted to become an apprentice haircutter.

Several months later Gary Johnson and I visited Catherine at an apartment she shared with several outrageous drag performers just off Yonge Street above a vintage clothing store on Charles Street, close to the fledgling gay village. The drag queens arrived home after an afternoon of shoplifting and chain-smoked from long cigarette holders while modelling skin-tight outfits, make-up, and false eyelashes while giving us camp schtick and flirtatious side glances we did not respond to. Cathy made pots of tea and chatted while critiquing each wardrobe change. The afternoon was an decadently eye-opening quintessentially Felliniesque encounter.

At the time, I was living in a large communal house on Clarence Street with a hippie vibe in London, Ontario, within walking distance of the Keg. One of the servers, Dorey, from the Keg and her boyfriend, shared the house with another couple. They offered me a large room on the second floor with house privileges. I remember Catherine visiting from Toronto. Dorey and Catherine went to school together. Catherine was flawed, vulnerable, and had too much to drink that weekend and things with the other housemates became contentious.

I also remember being excited, dressed, and ready for my first gay dance at UWO with Gary Johnson, who also worked at the Keg with us and became a close friend of mine until he died of AIDS in 1995.

Gary Johnson and I came to the Toronto gay scene when gay bars were beer halls like the Parkside Tavern, St. Charles Tavern and the cocktail bar the Quest on Yonge Street in a city that was not encouraging or respectful to the gay community. There was also the unlicensed all-ages gay male dance club, the Manatee, where I first heard Gloria Gaynor's debut recording of Honey Bee. Catherine was always a supportive and vocal ally of gay men and had many lesbian and bisexual friends.

Catherine was apprenticing asymmetrical cuts and styling hair at Bruce of Crescendo in the Commerce Court Building with several eccentric Warhol-like characters in the late 1970s. I would drop by to see her every time I took the train to Toronto for a day or a weekend. Sometimes we would meet up after work for cocktails or meet at Bemelmans a trendy Manhattan-style bar and restaurant on Bloor Street West.

Catherine moved back to London in 1980 to attend Western University and get her BA. She moved into a three-story walk-up on Western Road. I remember sending her a big bouquet of pastel spring flowers. In those years, we met at Singapore, a cocktail bar below Sorrenti's restaurant across from the Grand Theatre. The intimate lounge was an oasis of smoky cosmopolitan seduction and sophistication with an adjoining secluded back room complete with two Moorish-inspired tented booths. Doyennes Tania Auger and Tracy Leckie presided over the bar. A core group of restaurant people from Gabriele's and Sorrenti restaurants and actors like Brent Carver and Susan Wright frequented the bar after theatre performances. Signapore became our haunt.

In the summer of 1985, I sublet Catherine's main floor apartment across from the Prune Restaurant in Stratford while she was in France. Two Shakespearian actors were living in the apartment above me. It was convenient because I was working at the Church Restaurant that summer and Catherine did not have to pay rent well she was abroad. Another time Catherine was on sabbatical in a French speaking village on a river in the Eastern Townships in Quebec. I loved to visit her for a week in Stratford in the winter. We were often snowed in and would spend the evening in the Jester's Arms, a few blocks from her apartment. I have memories of unplowed roads, giant snow drifts and schools being closed.

Catherine invited ten people to her and George Jackson's wedding. Tracy Leckie and I received verbal invitations to the nuptials, and then a more formal embossed card, neither attended. They were married at The London Hunt and Country Club, a local institution, for over one hundred years. I was intimidated by her parents and the venue. I was certain I did not have the appropriate formal attire or demeanour. I’d like to say that I saw the writing on the wall, as far as their marriage was concerned but I didn’t.

Catherine's father, George Bowie, was past president of the UWO Alumni Association, London Regional Art Gallery and founding member of the University of Western Ontario Spring Festival and Foundation Western. George received the University of Western Ontario Alumni Award of Merit in 1985. He was the president of the London Hunt Club, The London Club and the Lamb's Club. Both families were friends and well-connected.

March 20, 1991

Dear Bryan,

The cleaning ladies are coming, so I'm cleaning up for them. It's given me another chance to marvel at all the beautiful (and nutty) things you've given me over the years. In case you were in doubt, I am filled with gratitude and wonder at your generosity. So many thanks still. Geo and I drove by your beautiful little palace on Palace Street. Cute as a bug's ear. Saw Gary and Barry on our March break. Most Fellini. I will see you at the end of April. Susie, Kato, Terry and I are lunching at La Cucina. I'll call to reserve when I have more details. I love you, Cathy xox.

Gary remembers George and Cathy visiting their consignment shop in a repurposed old pig barn on the outskirts of Chesley, Ontario. George gave them a business card for his Orbit Bakery venture in downtown Stratford.

The London Free Press, Monday February 8, 1993

The woman's husband, George Jackson, a 37-year-old Orbit bakery operator, has been charged with first-degree murder. He was remanded Monday in custody until Friday. Inspector Bill Forbes of the Stratford police said Cathy's body was discovered in her home at 3:25 am. Saturday by police. She had been shot once. But because it is considered evidence, Forbes wouldn't comment on the type of gun used or the location of the fatal wound. He said the couple had no children and lived alone. Juliet principal, Ron Aitken of St Marys, said Sunday night, school officials spent the day notifying staff and former staff members of Jackson's death. Aitken said Jackson was in her tenth year at the school where she taught French to Grades four to seven. He described her as an amicable person and had many friends on staff. Another teacher, William Leney of Stratford, said he had known Jackson since she started teaching at Juliet. “She was a very pleasant person with a good sense of humour, quiet.”

“She was a very gentle person” classroom assistant Nora Darlington said Monday. Darlington who described herself as a close friend of the woman, said the shooting came as a shock to those who knew her. “She was a quiet and understanding person.” Others spoke of her friendliness and sense of humour.

"Every detail of her life had been minutely examined and besmirched her character. It should be the law the murder victim is not to be on trial. Catherine's character had nothing to do with her death, and how they portrayed her is not who she was. They wanted to destroy Catherine's character so George would receive a reduced sentence."

"Like many intimate partner homicides, Catherine's character was stigmatized, slandered and dragged through the mud regarding her drinking and past sexual history by the court."

"Responses to victims of intimate partner homicide should not be allowed to revictimize the deceased individually by the abuser or through the courts. Evidence from various sources suggests that most wife killings are by a man accusing his partner of sexual infidelity, her decision to terminate the relationship, and his desire to control her."

February 24, 1993

Dear Bryan,

Thank you for your letter of sympathy that arrived this morning. There were two wonderful services for Cathy in Stratford. One was put on by her friends from Stratford and Toronto. One service was held in a lovely older Anglican Church in Stratford, and her friends and other teachers spoke. There was also an exceptional singer who sang Over the Rainbow with a guitar accompanying. The pupils at her school had a remembrance in the gym and had written a song for Cathy, plus letters and poems. These were put in two books for us to take home. Cathy will be greatly missed. We loved her very much and were very proud of her. Cathy said you were in Europe but didn't say when you were coming home. We are going to Florida but will be back on April 2. If when you come home, and you would like a copy of the service for Cathy, please call.

Sincerely, Margaret & George Bowie.

A student wrote an illustrated story called Madame Jackson's Bicycle that Catherine's mother sent to me in England. She said, "One of my favourite memories of Mme. Jackson is the bike she would ride to and from school every summer day. Sometimes she would ride by me while I was walking to school, and she was always friendly with a pretty smile. Mme Jackson had a basket on the back of her bike right above her back wheel. She would usually have her schoolwork in it and sometimes a long loaf of bread from her husband's bakery. When Mme. would arrive at school, she would always lock up her bike at the flag pole at the front of the school. Thanks for the memories. Your friend forever, Laura Blouse 8C

Others said she was pleasant, well-liked and had a keen sense of humour. They didn't know why anyone would want to kill Catherine Mary Jackson, a woman who impressed fellow teachers and pupils at the Juliet campus of Romeo and Juliet elementary school in Stratford. The Care Team from the Perth County Board of Education was at the school Monday to counsel teachers and pupils, two days after Jackson, forty-one, was shot to death in the bedroom of her Front Street home.

Sheri McDonald wrote on Facebook a year ago. "Miss Jackson taught me, French at Juliet in 1983. Blonde hair and very sweet -- she made French enjoyable!”

Another former student wrote, I remember Mrs. Jackson, too. She was really lovely, especially considering Juliet had many straight-from-hell students at the time. I remember the day of the murder. My mother and I attended Shakespeare Public School for an event because my brother attended, and they evacuated the whole school."

Someone told me, "In a fit of jealousy, George shot Catherine after an evening of drinking."

Neighbours on Front Street reported seeing police vehicles outside the house, cordoned off the property with black and yellow tape at about 8:30 am Saturday to notify the public that an investigation was ongoing and that particular area was restricted. It drew a crowd of onlookers.

George's mother, Barbara, was a warm and talented artist and photographer and surrounded herself with many friends from the art community in London. My business partner Betty was a friend of Barbara’s. They were both painters and enrolled in a special adult art program at H.B. Beal Secondary School with classmates Sue Boone and Nan Paterson.

At Barbara's suggestion I wrote George at Joyceville Penitentiary north of Kingston, Ontario.

He responded, "You have no idea what your letter received yesterday means to me. I know how difficult it must have been to write. First letters in this situation are notoriously tricky on both sides of the fence. Fortunately, it is possible to have privacy here because after I read your letter, I was overcome by conflicting emotions dwelling silently within me, and I wept briefly in my cell. It wouldn't do to have the other chaps see a thing like that, for we are men here. I think they were tears of sorrow, first for the whole sorry mess, the significant loss, and how I have hurt you and many others."

George wrote, saying, "The person writing is vastly different than the person they took into police custody." He was still devastated by the events of that fateful morning. "Believe me," he said, "no one is more shocked than I am. I had no intention of surviving the day, and plans to kill myself were thwarted. I wouldn't want to live in a world where I had taken Cathy's life. No man has ever wished to be dead than I did in the days that were to follow. There is no moral, spiritual or intellectual basis for the act of manslaughter, so how do I accept it? Yet that is my task."

The words "the act of manslaughter" have stuck in my craw for thirty years. It seemed so inauthentic and telling. A lack of accountability and the appearance of denial. I wanted to ask George to explain to me the difference between manslaughter and murder. George mentioned all the people he hurt.

"Apart from missing Cathy very much, it certainly sounded bizarre in my statement to the judge at my sentencing."

"However, the people I have hurt the most are, of course, the people who loved me the most, and here is where the most appalling, horrifying reality resides, Cathy's parents. Thinking of what I have done to these wonderful people is paralyzing. They looked at me as a son. I called them Mom and Dad—no wonder I didn't want to be around for this. But here I am. I live and breathe, which is unfair to Cathy but which exists as a fact. I've had a year to look at this, at what happened, at how and why. I've looked at this tragedy from every conceivable angle. My heart wants to continue this letter, but my head tells me not to. There is much time. I possess that most elusive commodity for the first time in my life."

"But I can only close by reiterating how much it means to hear from you. You and I shared many sane and sober moments between the rest, and I have been thinking about you a lot, wondering. While I can hardly imagine the word love would mean automatic forgiveness. I have the luxury of starting somewhere far from London and its environs."

After George secured an early release from prison, his mother asked my business partner, Betty, and me if bringing George to our restaurant, Blackfriars, would be okay for lunch. Betty knew Barbara well as they were both artists and had returned to University as mature adults. Barbara would bring a lot of catering business to the restaurant. Betty worked with George at the Black Swan fifteen years earlier and remembered him as laid back, well-mannered and nice to work with. She liked talking to him. There was a core group of restaurant people who chummed around and Betty and George were part of that group. Betty had only met Catherine once at the Jackson family cottage. Betty had been deeply shocked by the news of Catherine’s murder.

After considerable consternation, we agreed we could handle it. I was overcome with an overwhelming sense of disloyalty to Catherine.

A rehabilitated George was on his best behaviour and appeared remorseful and contrite in Barbara’s company. He asked Betty and me to join him later in the evening at Chaucer’s next to the Marienbad. He was meeting up with Uncle Billy a well-liked taxi cab driver. That evening confirmed my suspicions and left me with a sour taste in my mouth. I had given him the benefit of the doubt but he just was not a stand up guy. George’s behaviour was hard to interpret as genuine repentance, and appeared as part of calculated machinations to have his sentence reduced. I never saw or spoke to him again. Provocation is the only defense which is exclusive to homicide. As a partial defense, it serves to reduce murder to manslaughter when certain requirements are met.

The Canadian Department of Justice has described crimes of passion as "abrupt, impulsive, and unpremeditated acts of violence committed by persons, who have come face to face with an incident unacceptable to them, and who are rendered incapable of self-control for the duration of the act."

A person committing second-degree murder, while not premeditated, fully understands their actions and kills someone anyway. Manslaughter involves a circumstance that may cause a reasonable person to become emotionally disturbed or considered a murder fueled by passion or impulse. A crime of passion in widespread usage refers to a violent crime, especially homicide, in which the perpetrator commits the act against someone because of a sudden strong impulse such as anger or jealousy rather than a premeditated crime.

BOWIE: ONE IN A MILLION documentary chronicles Catherine's last hours and relates how she ended up on trial as the defendant ironically seeks to prove her responsible for her death. George ultimately got off with a light sentence, which is common in Canada. The One in a Million video presents a collage of the numerous cases in Canada when husbands or lovers have killed their mates, thus making Bowie one in a million Canadian women subject to male violence. Shown at the Toronto International Film Festival in 2000, this searing indictment of society's failure to deal with intimate partner violence pays homage to Cathy Bowie. Some called her a gentle woman. A documentarian called her a vibrant young woman whose life became a headline story and faded into a statistic.

BOWIE: ONE IN A MILLION is a short documentary about domestic violence which premiered at the Toronto Film Festival in 2000, seven years after Catherine's death.

"BOWIE: ONE IN A MILLION This searing portrait pays homage to Cathy Bowie, a vibrant young woman whose life became a headline story and then faded to a statistic after she was murdered in her home by her husband, George Jackson." - Spectrum Films

Janis Cole's BOWIE: ONE IN A MILLION is a compelling, personal film about her friend Cathy Bowie, who was killed by her husband, George Jackson, in an incident of domestic abuse. Using photos of the happy-go-lucky Bowie, Cole powerfully illustrates the justice system's failure to deal with violence against women, making her point with intelligence and clarity.

Quote about BOWIE: ONE IN A MILLION

"This devastating short film speaks to the mature economy of Cole's recent writing, her enduring commitment to women, and the social injustices that must continue to be criticized and resisted." - Kay Armatage

When I heard about Janis Cole's documentary, I contacted her and obtained a VHS copy. I was surprised to see a photograph of Catherine and me in a collage in the film. I wondered how Janis had acquired the picture.

Cathy had many close friends, and four years ago, one of them sent me a friend request on Facebook and then messaged me a few months before the pandemic surfaced.

Bryan,

"I love having a glimpse into your life and seeing all your success. As you can imagine, I always get a little down this time of year, as there is no day I don't think of Catherine. My daughter Sadie's middle name is Catherine, and believe me, she has the same smile, beauty, big heart and naughtiness as her namesake. Saying that she has her namesake angel keeping an eye on her. I can't remember the exact day of her death. February 4, 1989? If you are ever in Waterloo, I would love to meet for a glass of wine or two and meet my wonderful wife, Cindy." -Susie

Susie, Thank you for contacting me. I have been thinking about Catherine all morning. There have been so many times over the years that I have wanted to reach out to you. I did not have the language to express myself and was afraid my grief was overpowering. I have never entirely recovered from the news. Mr. and Mrs. Bowie were not the warmest individuals, which complicated things for me. I was friendly with George's mother, Barbara as well. Catherine and I became steadfast friends working at the Keg in London in 1973. Dorey was working there as well. It is only in the last decade or so that Dorey and I have become reacquainted. I have never brought up the subject of Catherine with her. I am delighted to hear that Sadie's middle name is Catherine. I wanted to be more articulate than this. Catherine passed away on February 6, 1993. I will get in touch with you soon. Thank you for this. -Bryan

Someone recently posted On Reddit in 2023, "The French teacher and her husband had broken up and still lived in the same household. I remember he received seven years because she kept a diary which said, "How far can one go before breaking or something to the effect..."

Margaret and George Bowie established an award to honour the memory of their daughter, Catherine Mary Bowie (BEd'83, HBA'82, BA'80). The award is presented to a full-time undergraduate student entering the third or fourth year of an Honours Bachelor degree in either an Honours Specialization in French Studies or a double Major including French. Recipients needed a minimum academic average of 75 percent.

During the pandemic, I visited Catherine's grave at Zion 7th Line cemetery on Cobble Hills Road, close to Ingersoll, where her mother was born. I had visited the graveyard before the headstone was over the grave. Both her mother and father are now buried beside her.

Betty said George told her the night we met him at Chaucer’s he should have married her instead of Catherine. Betty said it was a chilling thought.

Bryan, thank you for sharing this story. Sometimes I think about not just the moments leading up to someone's death, but the days and months or even years. And inevitably, I'm always left partly in both wonderment and a state of 'no wonder that's the case.' Which is an interesting dicothomy. Your narration helps bring clarity to that dichotomy. :)